Download the paper slide rule Practice with the virtual slide rule

A brief history of the slide rule

The slide rule made possible to design the world before computers.

This is just a brief history of the slide rule, the full version can be freely downloaded. A simple tutorial is at the end of this page.

"Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed"

with these words Armstrong announced the landing on the Moon.

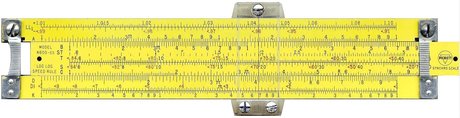

One of the on-board computers was a pocket slide rule, supplied to all the Apollo missions.

Invented in 1622 this tool came in space.

An history long forgotten, overtaken by a digital age that seems to exist forever.

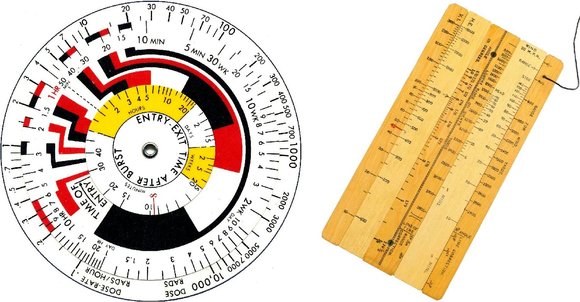

Pickett N600 ES sliderule, in use on the Apollo's missions

INTEL 4004 microprocessor was designed by Federico Faggin in 1971.

At the time the computers were huge, they needed operator to be used and to access them you had to book in advance.

The designers calculated everything with slide rules and eventually asked for computer verification at the end of the work.

The structural calculation of airplanes, spacecraft, etc. required absolute precision. Circular slide rules were used, whose long scales guaranteed exact results.

1971: Gilson slide rule and 4004 processor signed by Faggin

In 1971 the 4004 was mounted on a cumbersome Busicom calculator, but already the following year appeared the HP 35, the first portable scientific calculator. The era of slide rules was over, let's see it briefly.

The slide rule

In 1617 John Napier revolutionized mathematics by discovering logarithms. Complex calculations could finally be carried out relatively quickly.

In 1620 Edmund Gunter drew the logarithmic scale

placing the numbers on a ruler at a distance from the origin proportional to the value of their logarithm.

Instead of looking for the logarithms in the tables just add them with the help of a compass.

Particolare di un righello di Gunter, ca. 1790

This instrument remained in use until the early 1900s, despite the fact that the slide rule had already been invented in 1622.

In fact, in that year William Oughtred duplicated the logarithmic scales by sliding them parallel.

An innovation that allows quick and direct reading of the result.

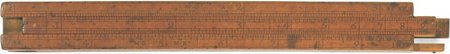

In 1654, just few years after the invention of Oughtred, Robert Bissaker made the "Gauging Rule", with 4 slides, specialized in measuring the contents of the barrels of wine, beer or spirits and calculate the tax burden.

A very succesfull instrument that was marketed for over 300 years.

The Gauging Rule, half of the eighteenth century

In 1677 Henry Coggeshall created the "Carpenter's Rule", mounted on two wooden rulers with the gradation in inches, the central sliding scale in bronze and several other scales to solve various problems.

It is a combined instrument that has allowed the common people to measure and calculate, remained in use until the beginning of 1900 in shipyards and workshops.

Carpenter's Rule, ca. 1840

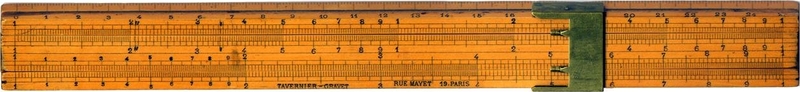

At the beginning of 1700 there were slide rules specific to all the needs of the time.

The Carpenter's Slide Rule was used to find the volume and weight of shipments, the Gauging Rule to calculate the taxation of beer barrel.

The Gunter's Scale allowed a great work: the mapping of the United States.

Gauging Rule, ca. 1820

Towards mid-800, however, there was a pressing need for computational tools not only specialized in tax or workshop use.

Essentials for the design of steam engines and the development of railroads, the generic slide rule began to appears.

Soon became the secret weapons of the industrial revolution.

Charpentier, ca. 1880, one of the first generic slide rule

The golden age

In 1859 the French artillery lieutenant Amedee Mannheim perfected the scales introducing the movable cursor. the modern model was born.

With the Mannheim model appears the cursor, ca. 1860

Around 1920 the slide rule had assumed its final form.

Einstein used it to develop the theory of relativity, Marconi for the radio.

Fermi for the atomic bomb, Korolev for the Sputnik program and Von Braun for the engines of the Saturn V, the Apollo vector.

The model preferred by Einstein, ca. 1930

In order to improve accuracy, proportional to the length of the scales, where produced models very large, also circular or cylindrical.

Fowlers, ca. 1910

Fuller, 1921

Large cylindrical slide rule, ca. 1936

The slide rule in the war

The modern slide rule was made by the French lieutenant Mannheim to maximize the range of his guns.

The slide rule has a glorious track record and it is still in force in armies.

Does not need to be recharged and can be launched from 20 meters in height, continuing to function.

Finally, during the Cold War, a Soviet nuclear attack was feared and only the slide rules can operate in contaminated environments.

In critical situations, reliability is essential.

Slide Rule to measure the exposure to radiation and sniper model

Slide rules were used by gunners to solve the problems of the shooting triangle.

They were also used in meteorology to analyze the data provided by the sounding balloons.

Forecasts were essential in the planning of the air attacks and also the date of the "D-Day" was chosen according to the weather report.

Preparation of the meteorological bulletin

Launching torpedoes requires a lot of calculations. Italians and Germans used a simple circular slide rule, the American electro-mechanical models to automatically found the best shooting solution.

US automated sliderule and the simple European model

Modern bombing required perfect determination of targets, often nocturnal or obscured by clouds.

In the ground bases the slide rules were used by personnel tactical support to draw the map of the air battles.

Tactical calculations during the Battle of Britain

The needs of air navigation also led to the E6B aeronautical sliderule.

This instrument proved immediately irreplaceable and lived a long career.

It remained the only computer of board up to the first Jumbo Jet and is still used today in small airplanes.

I have dedicated a specific section to it.

The first E6B, the progenitor of a series still on the market

The twilight of the analog era

The first computers appeared around 1946, but they were huge and expensive, the same IBM planned to sell up to four a year, and the slide rule seemed irreplaceable.

Nobody imagined a world without the sliderules: they served to housewives in the kitchen, to tracing the routes on the ship "Star Trek". Appeared on the cover of Playboy, were also proposed as cufflinks and tie clips.

"Miss Slide Rule", ca. 1950

Walt Disney had a simplified model for the children, was built in Braille for the blind, with scales dedicated to solving statistical problems and also in hexadecimal, octal or binary for computer programmers.

Hexadecimal model for computer programmers

It was the laptop of the era, always sticking out of engineers' pocket. A true sign to identify the category.

In 1955, after 9 years of tests, one of the most revolutionary aircraft in history was delivered: the Boeing B52 Stratofortess, a long-range nuclear bomber jet.

Designed with slide rules, it has a modern and innovative flexible wing structure.

Produced until 1962 it is so well conceived that it is still in service, updated in electronics.

Its disposal is in fact scheduled for 2040.

The B52 and the slide rule used by Boeing

Approximating calculations for excess created the myth of the "Olde Good Things", but the modern structural analysis required now exact results, thus promoting the development of electronic calculators.

These were of course designed using sliderules.

Robert Ragen said to have consumed two to realize in 1963 its revolutionary "Friden 130".

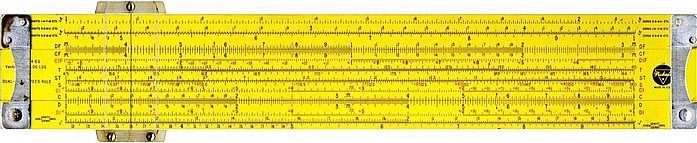

The latest slide rules had more than 30 scales

To provide economical and precise tools, were designed slide rules that projected a virtual logarithmic scale several meters long.

Unfortunately, they were still too expensive to be successful.

Salmoiraghi projection slide rule, probably

the best analog calculator ever built

In 1969 the sliderule was used on the Apollo 11 landing on the Moon: a very long career which began more than 350 years before.

However these tools are only accurate to three decimal places and the engineer needed to make estimates with the help of their experience.

From the seventeenth century to the Moon, a really long career

Finally in 1972 the Helwett Packard, advertising it as "Innovative electronic slide rule", put on sale the first economic scientific calculator, 50 times smaller than the competitors and so modern that it is still on the market.

The capabilities of the new HP 35 were indispensable. Forbes cites it among the 20 objects that have changed the world, and analog computers disappeared from the market in a flash.

From 1972 only electronic in space

The HP 35 uses the logical principle of Reverse Polish Notation (RPN), designed in the '20s by Jan Lukasiewicz, which allows to describe any formula without the use of parentheses.

Before you enter the operands and then operators: (4 + 5) x 6 becomes 4 ENTER 5 + 6 = x and therefore lacks the key =.

Try the Java simulation of the HP35, Neil Fraser

![]()

Calculate the hypotenuse of a right triangle with legs of 3.4 and 4.3 cm

The RPN eliminate the problems due to parentheses and operator precedence (first division, then the addition etc..).

The time to look the scales for interpreting the results was ended.

The slide rule today

But our "hero", reliable and environmentally friendly, it is always necessary to pilots and military and perhaps the adventure is not over yet.

The Asimov' science fiction novel "The feeling of power", assuming a return to the old methods of calculation, ends with these words:

"Nine times seven, thought Shuman, is sixty-three, and I don't need a computer to tell me so. The computer is in my own head. And it was amazing the feeling of power that gave him".

First computers were not powerful, but able to replace 150

engineers equipped with sliderules: their time had come

Logarithms and the basis of the slide rule

The mathematician John Napier discovered in 1614 the logarithms, published in "Mirifici logarithmorum canonis descriptio", capable of expressing any positive number via powers.

Since the product of two powers with the same base is a power with the same base and exponent given by the sum of the exponents, with logarithms multiplications and divisions can be made as simple additions and subtractions.

To multiply two numbers just look out for their logarithms and add them together: the result is the number whose logarithm correspond to the sum.

In practice the logarithm of a number in a certain base is the exponent to which the base must be raised to obtain the number.

The logarithm of 10,000 in base 10 is 4 (104 = 10,000) and 10,000 x 1,000 become 104x103 = 104+3 = 107 = 10,000,000.

Multiplication and division of exponents allow to find squares, cubes and roots.

Things get complicated when dealing numbers other than 10: we need a volume with more than a million values.

The tables had a very long life as they were cheap and their precision made them indispensable for astronomers and navigators ap to ca 1975.

With logarithms we are unable to work quickly as the consultation of the tables is very laborious.

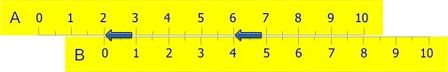

In 1620 Edmund Gunter, to expedite the proceedings, designed the logarithmic scale by placing numbers on a ruler at a distance from the origin proportional to the value of their logarithm. Here is the table:

Now we can try to construct the scale: the 1 is the starting point, the 2 is located at 3.01 cm, the 3 to 4.77 and so on up to 10.

We can therefore represent each number as we can read, for example, the number 3 as 30, 300, 0.003, 0.3, etc.

![]()

How far it is possible, for reasons of space, we now add the minor divisions (logs between 1 and 99).

Instead of search the logarithms in the tables we can simply add them with the help of a compass.

Calculating with a compass was however laborious, slow and difficult.

In 1622 William Oughtred marked the logarithmic scales on two sliding parallel rulers.

An innovation that allows the direct reading of the result.

The slide rule was born.

The sliderule, being an analog instrument, replace the mathematical functions with linear measurements. To show how it works let's start to see how we can execute an addition using two common metric rules.

To add 2 and 4, align first the 0 of the rule B with the 2 of the rule A.

We have set 2+ and the sum can be read on the mark of slide A, corresponding to the second addendum.

To add 2+6 we don't need to move again the rule (set on 2+), but just read the sum directly on the figure 6 of the B rule. To subtract, we use the opposite proceeding.

From the accuracy of the construction depends the precision of the results but, also dividing further the scales, it is not possible to operate with numbers greater than 100.

It 'is therefore clear that, as regards the addition and subtraction, the slide rule is much less practical than the abacus and to any other type of calculator.

This system, however, becomes very powerful if the scales are drawn using the logarithmic succession that we have seen previously.

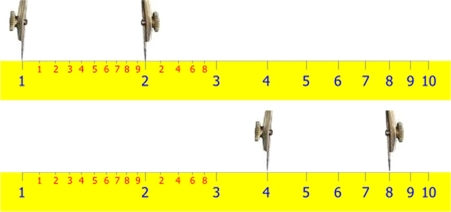

To perform 2 x 4 we align the 1 of scale B in correspondence of 2 in scale A and the result can be read on the same scale above the 4 of scale B.

We now have a tool that can perform multiplication. The previous picture also shows how to perform 8/4. Just put the 4 of scale B under the 8 of scale A and read the result on the same scale above the 1 in scale B.

The sliderule allows quick calculations thanks to the ease of adding logarithms by sliding two logarithmic scales over each other, but the first models invented by Edmund Gunter in 1620 were not so practical.

The scale is only one and to perform 2 x 4 we open the compass between 1 and 2 and then, keeping the same aperture, we put a tip on 4:

the other tip will indicate the result and to divide we use the opposite proceeding.

There are also some disadvantages. If we want process 4x3 the slides are positioned as follows:

The total is now located out of the scale. To solve this problem, we need to use the 10 of the rule B, instead of the previous 1:

So we obtain 1.2, but the right total is 12: the slide rule gives only the numbers and how to locate the dot or how to add ten or hundreds we must find by ourselves.

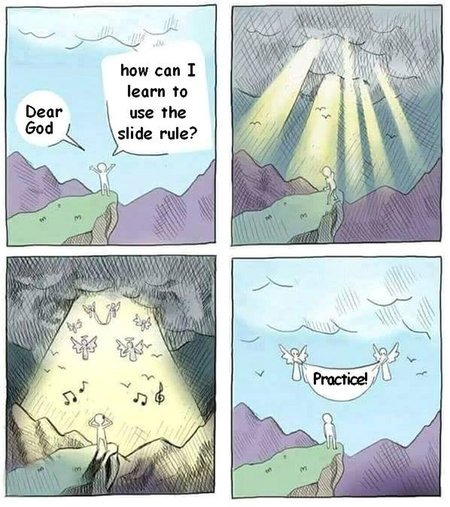

This was just a brief outlook, but the slide rule has many other scales and can reach the computing power of a modern calculator. His only flaw is the poor readability. The secret is: practice, practice ...

Practice with this slide rule emulator

Sliderules Links:

Sliderule on Wikipedia

The Oughtred Society

The Slide Rule Museum

rechenschieber.org

Medical sliderules

1972 Pickett ad: 5 lunar missions!

© 2004 - 2025 Nicola Marras Manfredi